TM

Medical

Research

Chapter 64: Plato

Chapter 64: Plato (427-347 BCE) — The Idealist: Forms and the Academy

Plato's philosophy bridged metaphysics and empirical inquiry, fostering systematic inquiry and influencing medical ethics and holistic health.

Abstract: Plato, a monumental figure from the classical era, remains a cornerstone of Western philosophy, influencing various domains, including philosophy, science, and medicine. Born in Athens around 428/427 BCE, Plato’s work traversed metaphysics, ethics, and rationalism. He focused on the immutable realm of forms, advocating intellectual and philosophical inquiry to uncover underlying realities beyond the physical world, as depicted in his Allegory of the Cave. While primarily aligned with rationalism, his philosophy also acknowledged sensory experiences as catalysts for awakening innate knowledge, blending empirical and rational approaches. Plato’s insights contributed to the early stages of the scientific method, fostering systematic inquiry that evolved into modern scientific investigation. His philosophy extended to medicine, promoting a holistic approach to health by envisioning a symbiotic relationship between soul and body. Plato’s dialogues on justice, beneficence, and autonomy laid foundational stones for modern ethics. Through the Academy and his writings, Plato’s legacy continues to shape contemporary thought, affirming the quest for truth and virtue.

**

Introduction: Plato, a luminary of the classical era, is a foundational figure in Western philosophy. Born in Athens around 428/427 BCE, his intellectual pursuits led him to explore vast domains of thought, from ethics and politics to metaphysics and epistemology. As a pupil of the enigmatic Socrates and the mentor to the eminent Aristotle, Plato was a vital link in the philosophical chain of the Greco-Roman world. His dialogues, wherein Socrates often serves as the central interlocutor, employ a dialectical method to uncover truths about reality, virtue, and the nature of the good life. Perhaps most renowned for his theory of forms, which posits a realm of eternal and unchanging ideas beyond the physical world, Plato’s ideas have deeply influenced subsequent philosophical, religious, and literary traditions. As both a philosopher and founder of the Academy in Athens — the Western world’s first institution of higher learning — his legacy continues to resonate, shaping the contours of contemporary thought and discourse.

Rationalism: Plato’s philosophy is emblematic of the rationalist tradition, emphasizing the primacy of reason as the path to genuine knowledge. Rooted in his distrust of sensory perception, Plato believed that our senses often deceive us, presenting mere shadows of the true, eternal, and unchanging forms or ideas. For him, the physical world we perceive is a transient replica of this higher realm of forms, accessible only through intellectual and philosophical inquiry. Plato’s Allegory of the Cave in his work “The Republic” vividly illustrates this belief: prisoners confined to a cave, seeing only shadows on the wall, are unaware of the more real entities causing these shadows outside the cave. Just as the freed prisoner ascends to see the outside world and recognizes it as more genuine than the shadows, the philosopher, through the rigorous application of reason, ascends to understand the realm of the forms. In Plato’s view, this ascent is a journey of the mind, transcending sensory limitations to grasp eternal truths. For Plato, true knowledge is innate and recollective, requiring an internal, rational awakening rather than empirical observation. This rationalist stance would heavily influence subsequent philosophical thought, particularly the works of thinkers like Descartes and Leibniz.

Empiricism: While Plato is primarily celebrated as a rationalist, strictly categorizing him might oversimplify his rich philosophical tapestry. Indeed, while Plato emphasized the superiority of the realm of forms and the intellect’s capacity to grasp them, he did not entirely dismiss the value of sensory experience. In several of his dialogues, notably the “Meno” and “Phaedo,” Plato suggests that while our souls innately possess knowledge from before our birth, sensory experiences can act as catalysts that awaken or “recollect” this pre-existing knowledge. Empirical experiences, in this sense, play an auxiliary role in facilitating the mind’s journey to the truth. His “Timaeus” also presents a cosmology where the Demiurge shapes the material world using the forms as an ideal template, implying an inherent connection between the sensory world and the eternal truths. Though it’s clear that Plato prioritized intellectual insights over empirical observations, he recognized the intricate dance between experience and reason in the quest for knowledge. Still, compared to his student Aristotle — who would become a paragon of empiricism — Plato’s occasional nods to sensory experience remain subordinate to his overarching rationalist inclinations.

The Scientific Method: While Plato is predominantly renowned for his contributions to philosophy and metaphysics, his influence on the early stages of the scientific method cannot be understated. Plato’s insistence on the need for a structured approach to inquiry, grounded in reason and rigorous logical examination, laid foundational thought for the systematic processes that would later define scientific investigation. His Academy in Athens became a crucible for intellectual discussions in philosophy, mathematics, and early natural sciences. Key figures like Eudoxus developed their theories within its walls, embedding systematic inquiry into the fabric of Hellenistic intellectual tradition. Moreover, Plato’s emphasis on abstract forms and ideals indirectly stressed the importance of seeking underlying principles and patterns in the observable world, a key aspect of scientific endeavors. While he did not outline the scientific method as we understand it today, the dialectic method used in his dialogues — wherein hypotheses are proposed, examined, and refined through discourse — resembles the iterative process of hypothesis testing in modern science. Thus, while Aristotle is often more directly credited with influencing empirical study and observation, Plato’s emphasis on reason, abstraction, and methodical examination set vital intellectual precedents for the evolution of systematic inquiry.

Medicine: Plato’s contributions to medicine are indirect but profound, primarily rooted in his philosophical discourses about the nature of the human soul and body and their interconnectedness. Unlike his contemporaries, Hippocrates deemed the “father of medicine,” Plato did not engage directly with medical practices or techniques. Instead, his writings in dialogues like the “Timaeus” present a holistic view of health, emphasizing the balance and harmony between the soul and body. For Plato, physical ailments were not just disruptions of bodily mechanisms; they were often intertwined with the state of one’s soul. This perspective underscored the importance of mental well-being in overall health, a notion that resonates with contemporary understandings of psychosomatic medicine. Moreover, in “The Republic,” Plato discusses the ideal society’s physicians, arguing that they should cure ailments rather than merely alleviate symptoms and suggesting that sometimes letting nature take its course might be the best approach. This is an early exploration into medical ethics and the philosophy of medical intervention. While Plato did not make direct advancements in medical techniques or knowledge, his philosophical musings laid a foundation for a more holistic, ethical, and soul-centered approach to health and wellness.

Ethics: Plato’s philosophical endeavors deeply shaped the realm of ethics, and while he didn’t explicitly coin terms like patient autonomy (informed consent), practitioner beneficence (do good), practitioner nonmaleficence (do no harm), and public justice (be fair), his writings undeniably touched upon these principles. Plato’s “Republic” is an exhaustive exploration of justice, seeking to understand its essence and manifestation in individual souls and the broader polis. For Plato, a just person or society is one where all components (soul parts or societal classes) fulfill their appropriate roles in harmony. In the medical and ethical context, this harmonious approach can be seen as a precursor to beneficence — acting for the benefit of others. Furthermore, in various dialogues, Plato’s emphasis on the importance of the soul’s health and the dangers of leading an unjust life can be extrapolated to the principle of nonmaleficence — ”do no harm.” The Socratic dialogues, where individuals are encouraged to question, reflect, and understand the reasons behind beliefs and actions, resonate with the principle of autonomy, championing the individual’s right to informed, self-directed decision-making. While rooted in metaphysics and virtue ethics, Plato’s ethical vision provides foundational insights into these core ethical principles, which have since evolved and adapted within various professional and societal contexts.

Conclusion: Plato’s intellectual breadth and depth have etched an indelible mark on the annals of human thought. Transcending the boundaries of philosophy, his ideas have touched diverse realms — from ethics and epistemology to science and medicine. Central to his philosophy is the belief in an immutable realm of forms, shaping his rationalist and, to a lesser extent, empiricist tendencies. Through his allegories and dialogues, Plato established the bedrock for systematic inquiry, underpinning the foundations of the scientific method. His holistic perspective on health, intertwining the soul and body’s well-being, laid philosophical underpinnings for a more comprehensive approach to medicine. Above all, his exploration of ethical constructs — justice, beneficence, and autonomy — has sculpted moral discourses that continue to guide societal decisions today. Plato’s legacy endures through the Academy and his writings, reminding us of the timeless quest for truth, goodness, and the essence of existence. His multifaceted contributions continue to challenge and inspire, offering intellectual nourishment to past, present, and future generations.

Plato’s Legacy: Established the Academy and introduced the theory of Forms, asserting that true reality consists of eternal and unchanging ideas rather than the material world. This perspective profoundly influenced subsequent philosophical thought.

**

A Closer Look

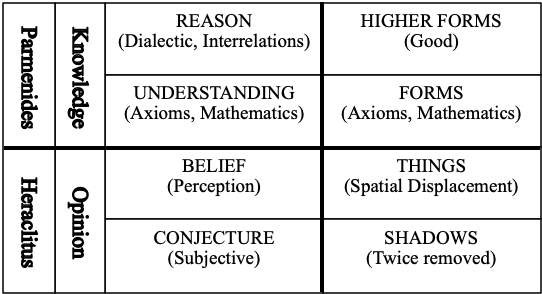

Plato’s Knowledge: Divided Line

Abstract: In exploring Plato’s philosophical doctrine, this narrative navigates the nuanced journey from the mutable world of sensory perception to the immutable realm of Forms, representing a synthesis of Heraclitus’ and Parmenides’ seemingly contradictory philosophies. Through a meticulous analysis of Plato’s Divided Line, the research delves into the progressive stages of knowledge: Conjecture, characterized by transient shadows of reality; Belief, which introduces space as a conduit for the physical manifestations of abstract Forms; Understanding, the realm harboring mathematics and scientific laws rooted in the physical world yet constrained by unexamined principles; and finally, the pinnacle of Reason, where dialectic discourse facilitates a holistic comprehension of the universe, anchored in the immutable and unified Form of the Good. This study presents a holistic vista into Plato’s complex and revolutionary perception of reality, embodying both change and permanence, offering a comprehensive grasp of what Plato thought was the true nature of existence.

**

Plato’s philosophical journey led him to a fascinating conclusion that reconciled the seemingly contradictory views of Heraclitus and Parmenides. Heraclitus had posited that reality was in constant flux, while Parmenides had argued for an unchanging, eternal oneness. At first glance, these views were at complete odds with each other. Yet, Plato, the great synthesizer, proposed a resolution that was as elegant as it was revolutionary.

What if reality was not a monolith, as the Milesians had believed, but rather dual, as the Pythagoreans had proposed? This dual reality, according to Plato, consisted of a world of sense perception, which was in constant Heraclitian flux, and a nonphysical, nonspatial, nontemporal, immutable world of Forms, which was the unchanging and unmoving Parmenidian one.

In this framework, both Heraclitus and Parmenides were correct, but they spoke of different aspects of reality. The world of sense perception, akin to Heraclitus’ view, was ever-changing and could only provide us with Opinions at best. In contrast, the world of Ideas or Forms, echoing Parmenides, was unchanging and eternally one, offering us a realm of absolute Knowledge.

Thus, Plato’s philosophical journey led him to a profound understanding of reality that embraced change and constancy, both the physical and the metaphysical. Our journey takes us from the tangible to the abstract, from the seen to the unseen, into the heart of a unified and complete Knowledge.

Conjecture

In the realms of Knowledge and Opinion, Plato proposed a hierarchy. At the base of this hierarchy, we find Conjecture, which Plato considered to hold the lowest degree of Opinion. This level is populated by the shadows and reflections of physical objects, the ephemeral and subjective experiences twice removed from reality.

To understand this, let’s consider Plato’s concept of Forms. For Plato, the Form of an object is its true reality. It’s the perfect, unchanging essence of the thing, existing in a realm beyond our physical world. The physical objects we interact with daily are merely spatial displacements of these Forms. They are imperfect copies, participating in true reality to a much lesser extent than the Forms themselves.

Now, let’s take this a step further. Imagine a tree. According to Plato, the physical tree you see in the park is a spatial displacement of the Form of the tree. The tree participates in reality, but not as fully as the Form of the tree. Now, consider a picture, painting, or a reflection of the tree in a pool of water. These images are various representations or “shadows” of the physical tree, which is already a lesser participant in reality. Therefore, the tree’s picture, painting, or reflection is twice removed from the Form of the tree, participating in true reality even less than the physical tree.

Belief

When we see a tree, touch a stone, or smell a flower, we engage in an Opinion of Belief. We interact with the physical manifestations of the Forms, the perfect, unchanging essences in a realm beyond the physical world.

But how do these Forms, these abstract, ideal concepts, make their presence felt in our physical world? How do they cast their shadows on the cave wall of our reality to borrow an image from Plato’s famous allegory? This question led Plato to postulate the existence of a medium, a conduit through which the Forms are reflected or make their appearances in our world.

Plato named this medium “space.” It is the canvas upon which the Forms paint their reflections, the stage where the drama of our physical world unfolds. In Plato’s philosophy, space is not just a void but an emptiness to be filled. Space is a necessary medium in the interplay between abstract Forms and their spatial representations.

Yet, despite space’s crucial role, space remains a mystery. It is a brute factuality, existing without explanation or justification. Because space itself is not a Form or a representation of a Form, space is “unknowable” as all Knowledge is only of Forms, and space is not a Form. Space “is,” and it “must be.” It is the silent, unexplained enigma at the heart of Plato’s philosophical universe. The four basic Forms — earth, air, fire, and water — are the fundamental building blocks of the physical world, each representing its corresponding Form through spatial displacement.

Imagine each element as a unique geometric shape: earth as a cube (6-faces), “fire” as a pyramid (5-faces), water as an icosahedron (20-faces), and air as an octahedron (8-faces). These geometric shapes are not just random choices but the spatial configurations of their respective Forms. The Form of Fire, for instance, is not represented in a material pyramid but in a spatial one.

Plato’s philosophy doesn’t stop at these four solids. He further reduces them to two triangles — the half-equilateral and the half-square. In this sense, Plato’s philosophy is a form of extreme Pythagoreanism, where “things’ (spacial displacements) are numbers. In its most fundamental form, sense perception reduces to spatial geometry, and geometry, in turn, reduces to arithmetic.

Understanding

Crossing the divided line between Opinion and Knowledge, we now transition from Heraclitus’ world of spatial flux, where everything constantly changes, to Parmenides’ realm of immutability, where unchanging concepts reign supreme.

This third level of knowledge is the realm of Understanding, the domain of mathematics and scientific laws, that focuses on the enduring truths of abstract concepts. Yet, as we navigate this realm of Understanding, we encounter certain limitations.

Firstly, this mathematical knowledge and scientific law level rests on unexamined first principles such as axioms and postulates. These foundational assumptions underpin our understanding, yet they need to be more substantiated and taken as given without further inquiry.

Secondly, despite mathematics’ and scientific laws’ abstract nature, this level of knowledge remains tethered to the physical world. Take geometry, for instance. While it deals with abstract shapes and spaces, its roots are firmly planted in the spatial world we perceive around us. This connection to the tangible world, while providing a bridge between the abstract and the concrete, also limits the degree of abstraction we can achieve.

Lastly, while offering deep insights into specific areas, the realm of Understanding fails to provide a unified vision of the cosmos. It is fragmentary, offering us puzzle pieces but not the complete picture. Each mathematical theorem or scientific law provides a glimpse into the universe’s workings, yet they still need to merge into a comprehensive understanding of how everything works together.

Reason

Continuing our path across the divided line of Opinion and Knowledge, past the first level of Understanding, we now arrive at the pinnacle of Knowledge — a realm illuminated by the power of Reason and the method of dialectic. This level transcends the limitations of the ever-changing physical world of spatial displacement, offering a holistic vision of the universe — the Parmenidian one.

At this stage, we are no longer confined to the realm of concrete, changing, and particular objects of perception, a domain characterized by the flux of Heraclitus. Instead, we ascend into the realm of universal, abstract comprehension of unchanging concepts, echoing the immutability of Parmenides.

Here, we engage in dialectic, a form of discourse that seeks to establish true first principles. This is the realm that studies the Forms, the ultimate reality. At this level, all divisions and steps melt away, and we experience the Form of the Good, the ultimate unifying reality. This is the pinnacle of Plato’s philosophical system, a state of knowledge where we grasp the unity of all things and comprehend the true nature of reality.

Plato’s Knowledge: Physics

Abstract: In exploring Plato’s perspective on physics, we delve into his interpretation of the physical world as a realm fundamentally grounded in Opinion rather than true Knowledge, which is reserved for the unchanging, eternal Forms. Plato’s Theory of Forms conceptualizes the material world as a fluctuating space where individuals perceive sensory images, unique to the motions of their sense organs, as mere shadows or reflections of the true Forms. These Forms exist in a transcendent space — a resistant, largely unintelligible “Receptacle of Becoming,” unaffected by the temporal changes that characterize the physical world. Consequently, as per Plato, physics is viewed as a “likely story,” an acknowledgment of the existence of space and its manifestations, yet devoid of the comprehensive analytical grasp intrinsic to the understanding of the immutable Forms. This discourse underscores the limitations of empirical approaches in grasping the depth of Plato’s largely metaphysical and idealistic philosophy, which places supreme reality in the perfect, unchangeable realm of abstract concepts or Forms.

**

In the grand theatre of Plato’s philosophy, the ever-changing physical world of spatial displacement takes a backseat to the realm of the eternal and unchanging Forms. For Plato, if physics is about the Opinion of the physical world and its processes, and Knowledge is about the eternal and unchanging Forms, then physics is Opinion, not Knowledge.

Plato’s concept of sensible images is tied to his theory of Forms. He agreed with Protagoras that every individual perceives the world differently due to the unique motions of their sense organs. In this ever-changing flux, what we perceive are not the objects themselves but their reflections or shadows in a medium Plato called “space.” This “space” is the “Receptacle of Becoming,” an everlasting entity that provides a situation for all things that come into being, or more appropriately, Forms represented by spatial displacement. Space is apprehended without the senses, is resistant to rational analysis, and remains largely unintelligible as space is not a Form.

Thus, for Plato, physics is only a “likely story,” a narrative that acknowledges the brute factuality of space but cannot fully explain it.

Plato’s philosophical ideas, particularly his Theory of Forms, don’t lend themselves easily to the empirical and experimental approach of the scientific method as we understand it today. Plato’s philosophy was largely metaphysical and idealistic, positing that the highest form of reality exists in abstract concepts or “Forms,” which are perfect and unchanging and that the physical world we perceive is merely a shadow or imperfect copy of this ideal realm.

Plato’s Scientific Method

Abstract: Plato’s approach to scientific inquiry, grounded in ancient philosophy, carves out a unique and foundational position in the history of scientific thought. Central to this approach is deductive reasoning, a principle where conclusions logically follow from established premises, a method particularly influential in mathematics and theoretical physics. Additionally, Plato emphasized the significant role of rationality and dialogues, the latter serving to explore and refine complex ideas through discussion, resembling an early form of peer review seen in modern scientific approaches. Moreover, his Theory of Forms, albeit more philosophical, forms a developing conception of scientific laws, illustrating the immutable principles governing reality. Despite facing critiques, notably for its non-empirical nature and its focus on immutable Forms, Plato’s scientific method significantly influenced the evolution of scientific thought, laying the groundwork that fostered the development of structured, systematic inquiry seen in modern scientific methods. This methodology is a testament to the rich, diverse intellectual traditions that have historically shaped the pursuit of knowledge and scientific discourse.

**

Deductive Reasoning: At the heart of Plato’s scientific method is deductive reasoning, a process where conclusions are reached by logical inference from premises regarded as true. If the initial premises in a deductive argument are true, then the conclusion must also be true. This emphasis on logical consistency and sound argumentation is instrumental in developing numerous scientific areas, notably mathematics and theoretical physics. Plato’s focus on deduction can be observed in his mathematical investigations, where he stressed the importance of axiomatic systems, which later became foundational in geometry.

The Role of Rationality: Plato underscored the importance of rationality in understanding the world. According to his philosophy, the rational mind can access and comprehend the Forms, which are reality’s eternal and unchangeable truths. This deep-seated belief in rationality as the path to knowledge laid the groundwork for the rationalist tradition in philosophy. It influenced the scientific method’s focus on logic and systematic inquiry.

Dialogues as Method of Inquiry: In Plato’s works, dialogues often serve as the medium to explore and dissect complex ideas. These dialogues, characterized by deep discussions and examinations of various viewpoints, are an early form of peer review, where ideas are scrutinized, tested, and refined through discourse. This method aligns with the collaborative and critical spirit of scientific inquiry, where peer review has become a cornerstone in validating and advancing scientific knowledge.

The Concept of Ideal Forms: While the Theory of Forms is more philosophical than scientific, it contains elements that can be seen as antecedents to scientific laws. In Plato’s philosophy, the Forms represent reality’s perfect and immutable aspects, transcending the physical world. This notion bears semblance to the concept of scientific laws — unchangeable principles that govern the operations of the universe. Through this lens, Plato’s idea of Forms may be perceived as a philosophical precursor to the abstraction and generalization that characterize scientific theories and laws.

Limitations and Critiques: It is crucial to note the limitations of Plato’s approach from a modern scientific perspective. Plato’s focus on immutable Forms and his disdain for the mutable physical world can be seen as counter to the empirical basis of the scientific method, which relies on observation and experimentation. Furthermore, his reliance on “a priori” reasoning, without empirical validation, is often seen as a deviation from the empirically grounded methods that characterize modern science.

Conclusion: While Plato’s scientific method may not align directly with modern science’s empirical and experimental foundations, it has undoubtedly contributed significantly to the evolution of scientific thought. Through deductive reasoning, the focus on rationality, the use of dialogue as a method of inquiry, and the early notions of immutable laws represented by the Forms, Plato’s approach to understanding the world sowed seeds that would later flourish into the structured, systematic method of inquiry that is the scientific method. Plato’s philosophy is an important reminder of the deep historical roots and diverse intellectual traditions that have shaped the pursuit of knowledge and the development of science.

Plato’s Ethics

Abstract: In the intricate framework of Plato’s ethical philosophy, the notion of the Good and the Theory of Forms stands central, portraying a transcendental realm of immutable entities, of which the Form of the Good is the epitome, serving as a beacon of ultimate truth and knowledge. Plato advocates for cultivating virtues — wisdom, courage, temperance, and justice — positioning them as facets of knowledge essential in guiding individuals toward morally upright living. Central to achieving this moral living is the harmonious functioning of the soul, comprising rational, spirited, and appetitive parts, orchestrated through reason and an alignment with the Good. Underpinning this is a transformative educational journey, vividly illustrated in the “Allegory of the Cave,” aiming to nurture philosopher-kings endowed with wisdom and justice to lead society. This ethical outline is complemented by Plato’s moral psychology and the Theory of Recollection, suggesting that learning is a rediscovery of innate knowledge held in the immortal soul, steering individuals toward ethical conduct. Consequently, Plato’s philosophy delineates a path of personal and societal moral evolution, urging individuals to union with the Good, thereby fostering a society rooted in wisdom and justice.

**

The Good and the Forms: Central to Plato’s philosophy is the Theory of Forms, which posits a world of eternal, unchanging Forms or Ideas that exist beyond the sensible world. The highest of these Forms is the Good, the source of all truth and understanding. Every soul aspires to understand this ultimate Form of the Good, as it represents the pinnacle of truth and the ultimate object of knowledge. Understanding the Good forms the basis of ethical behavior, allowing one to align oneself with the highest form of good.

Virtue Ethics and the Role of Virtue: In Plato’s ethical framework, virtue is central. Virtue, to Plato, is a form of knowledge, the knowledge of the Good, which guides individuals to act justly and wisely. Plato identified four primary virtues:

Wisdom: The ability to judge what is true and right.

Courage: The quality that allows individuals to face fear and uncertainty with resolve.

Temperance (or Moderation): Mastering desires helps maintain a balanced life.

Justice: Often seen as the supreme virtue, it represents the harmony of the soul, where all its parts function in unity to achieve the good.

The Soul and Its Tripartite Division: Plato perceived the soul as comprising three distinct parts:

The Rational Part: Focused on acquiring knowledge and understanding the Forms, particularly the Form of the Good.

The Spirited Part: Driven by honor and a sense of duty, it assists the rational part in controlling the desires.

The Appetitive Part: Concerned with basic desires and physical pleasures.

According to Plato, ethical living is achieved when the rational part governs the soul, keeping the spirited and appetitive parts in check. This harmony of the soul, orchestrated by reason, leads to virtuous living and justice.

Education and the Role of Philosopher-Kings: Plato envisioned an ideal society led by philosopher-kings who have a profound understanding of the Forms and are thus equipped to govern justly and wisely. Through their deep comprehension of the Good, these leaders guide society toward justice and harmony. Education plays a pivotal role in nurturing individuals capable of understanding the Forms. This philosophical education, depicted vividly in the “Allegory of the Cave,” is a journey from the shadows of ignorance to the luminous world of knowledge and understanding, fostering a class of rulers who embody wisdom and justice.

Moral Psychology and Personal Development: Plato’s moral psychology revolves around achieving harmony within the soul through cultivating virtues and pursuing knowledge. Individuals are expected to undergo personal development, a lifelong process of aligning closer with the Good. This alignment fosters moral development, where individuals gradually become more virtuous, achieving a harmonious soul-state that resonates with the Forms’ eternal truths.

Ethical Implications of the Theory of Recollection: In Plato’s philosophy, learning is a form of recollection, as the immortal soul already possesses knowledge of the Forms from prior existence. This theory implies that ethical knowledge is innate and that learning is a journey of rediscovering this inherent knowledge, guiding individuals to live ethically.

Conclusion: Plato’s ethical theory, deeply integrated with his metaphysical and epistemological doctrines, offers a profound perspective on moral living. Through pursuing the Good and cultivating virtues, individuals can aspire to achieve a harmonious state of the soul, fostering a society that embodies wisdom and justice and nurturing the highest potentials of the human spirit.

Plato’s philosophy beckons individuals on a transformative journey from the realm of shadows and illusions to the luminous world of eternal truths, where the ultimate goal is to achieve unity with the Good, the highest pinnacle of ethical and intellectual achievement.

**

REVIEW QUESTIONS

True/False Questions:

1. Plato believed that the physical world we perceive is the ultimate reality, and the Forms are merely abstract concepts with no true existence.

True or False?

2. In Plato’s ethical framework, justice is considered the harmony of the soul, where all its parts function in unity to achieve the good.

True or False?

Multiple-Choice Questions:

3. Which of the following is NOT one of the four primary virtues identified by Plato?

a) Wisdom

b) Courage

c) Temperance

d) Honesty

4. According to Plato, the ultimate source of all truth and understanding is:

a) The Rational Part of the Soul

b) The Form of the Good

c) The Physical World

d) The Allegory of the Cave

Clinical Vignette:

5. A physician aims to treat not just the physical symptoms of a patient but also considers their mental and emotional well-being. This holistic approach reflects the influence of which philosophical concept from Plato?

a) The Allegory of the Cave

b) The Theory of Recollection

c) The Harmony of the Soul

d) The Theory of Forms

Basic Science Vignette:

6. Plato’s emphasis on rational inquiry and systematic investigation laid the groundwork for early scientific thought. Which of the following best describes how Plato’s philosophical approach influenced the development of the scientific method?

a) By relying solely on sensory experiences to understand the world

b) By emphasizing the importance of empirical observation without rational analysis

c) By promoting the use of deductive reasoning and logical consistency in investigations

d) By dismissing the need for structured inquiry and critical examination

Philosophy Vignette:

7. Plato's Theory of Forms posits that true reality consists of eternal and unchanging ideas, while the physical world is a mere shadow of these forms. How might this concept influence contemporary discussions on the nature of scientific laws and theories?

a) It suggests that scientific laws are merely subjective opinions with no objective basis.

b) It implies that scientific theories are unchanging and eternal, reflecting a deeper reality.

c) It encourages the idea that scientific laws are based solely on empirical observations without underlying principles.

d) It promotes the view that scientific theories should be constantly revised and updated based on new evidence.

Correct Answers:

1. False

2. True

3. d) Honesty

4. b) The Form of the Good

5. c) The Harmony of the Soul

6. c) By promoting the use of deductive reasoning and logical consistency in investigations

7. b) It implies that scientific theories are unchanging and eternal, reflecting a deeper reality

BEYOND THE CHAPTER

Plato (427-347 BCE)

- Plato: Complete Worksedited by John M. Cooper

- Plato: A Very Short Introductionby Julia Annas

- The Cambridge Companion to Platoedited by Richard Kraut

- Plato’s Knowledge: Divided Line

- Plato’s Theory of Knowledge: The Theaetetus and the Sophistby Francis M. Cornford

- The Divided Line and the Structure of Plato’s Republicby Gerasimos Santas (Chapter inHistory of Philosophy Quarterly)

- Plato’s Divided Line: Essay on the Meaning of Plato’s Thoughtby Nestor-Luis Cordero

- Plato’s Knowledge: Physics

- Plato’s Natural Philosophy: A Study of the Timaeus-Critiasby Thomas Kjeller Johansen

- Plato’s Philosophy of Scienceby Andrew Gregory

- Plato’s Cosmology: The Timaeus of Platotranslated by Francis M. Cornford

- Plato’s Scientific Method

- Plato’s Method of Dialecticby Julius Stenzel

- Plato’s Philosophical Method: The Use of Dialectic in the Dialoguesby Nicholas D. Smith (Chapter inThe Cambridge Companion to Plato’s Republic)

- Plato and the Method of Analysisby John Palmer (Chapter inPhilosophy of Science)

- Plato’s Ethics

- Plato’s Ethicsby Terence Irwin

- Plato on Morality and the Good Lifeby Gerasimos Santas (Chapter inThe Cambridge Companion to Plato)

- Plato’s Moral Theory: The Early and Middle Dialoguesby Terence Irwin

***

CORRECT! 🙂

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Aliquam tincidunt lorem enim, eget fringilla turpis congue vitae. Phasellus aliquam nisi ut lorem vestibulum eleifend. Nulla ut arcu non nisi congue venenatis vitae ut ante. Nam iaculis sem nec ultrices dapibus. Phasellus eu ultrices turpis. Vivamus non mollis lacus, non ullamcorper nisl. Pellentesque habitant morbi tristique senectus et netus et malesuada fames ac turpis egestas. Phasellus sit amet scelerisque ipsum. Morbi nulla dolor, adipiscing non convallis rhoncus, ornare sed risus.

Sed adipiscing eget nibh at convallis. Curabitur eu gravida mauris, sit amet dictum metus. Sed a elementum arcu. Proin consectetur eros vitae odio sagittis, vitae dignissim justo sollicitudin. Phasellus non varius lacus, aliquet feugiat mauris. Phasellus fringilla commodo sem vel pellentesque. Ut porttitor tincidunt risus a pharetra. Cras nec vestibulum massa. Mauris sagittis leo a libero convallis accumsan. Aenean ut mollis ipsum. Donec aliquam egestas convallis. Fusce dapibus, neque sed

Wrong 😕

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Aliquam tincidunt lorem enim, eget fringilla turpis congue vitae. Phasellus aliquam nisi ut lorem vestibulum eleifend. Nulla ut arcu non nisi congue venenatis vitae ut ante. Nam iaculis sem nec ultrices dapibus. Phasellus eu ultrices turpis. Vivamus non mollis lacus, non ullamcorper nisl. Pellentesque habitant morbi tristique senectus et netus et malesuada fames ac turpis egestas. Phasellus sit amet scelerisque ipsum. Morbi nulla dolor, adipiscing non convallis rhoncus, ornare sed risus.

Sed adipiscing eget nibh at convallis. Curabitur eu gravida mauris, sit amet dictum metus. Sed a elementum arcu. Proin consectetur eros vitae

TM